Port Arthur was once considered ahead of its time, but in reality was a brutal place. Photo: Thomas Huxley

Port Arthur was intended to be a state of the art prison, using new psychological incentives to reform inmates.

You’d never guess so, looking at its macabre remains today. It was a brutal place.

The British turned Tasmania into a penal colony in 1803, and to this day it is the penal period that many Australian’s recall about Tasmanian history.

Of course, the island’s history goes far beyond the short period of white settlement.

Tasmania and its surrounding islands were occupied by Aborigines about 40,000 years ago.

They were likely separated from mainland Aborigines about 10,000 years ago when the sea level rose to form Bass Strait.

Aborigines numbered 3000 to 7000 at the time of white colonisation. The Aboriginal population subsequently plummeted from war, intertribal fighting and the spread of infectious diseases.

The British penal colony was created partly to prevent claims to the land by the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars.

The island started its colonial life as part of NSW, but became a separate, self-governing colony called Van Diemen’s Land, named after Anthony van Diemen), in 1825.

Port Arthur penal settlement, 100km south-east of Hobart on the Tasman Peninsula, was named after Van Diemen’s Land Lieutenant Governor George Arthur. The settlement started as a timber station in 1830, but is better known its penal colony.

From 1833 until 1853, it was the prison for the worst British criminals, those who re-offended in Australia. Port Arthur had some of the strictest measures in the British penal system.

The prison was completed in 1853 and extended in 1855. The prison shifted away from physical punishment to psychological punishment. It was thought whippings hardened criminals, and did not fix immoral ways. So food was used to reward well-behaved prisoners. Punishment was a bare minimum ration of bread and water.

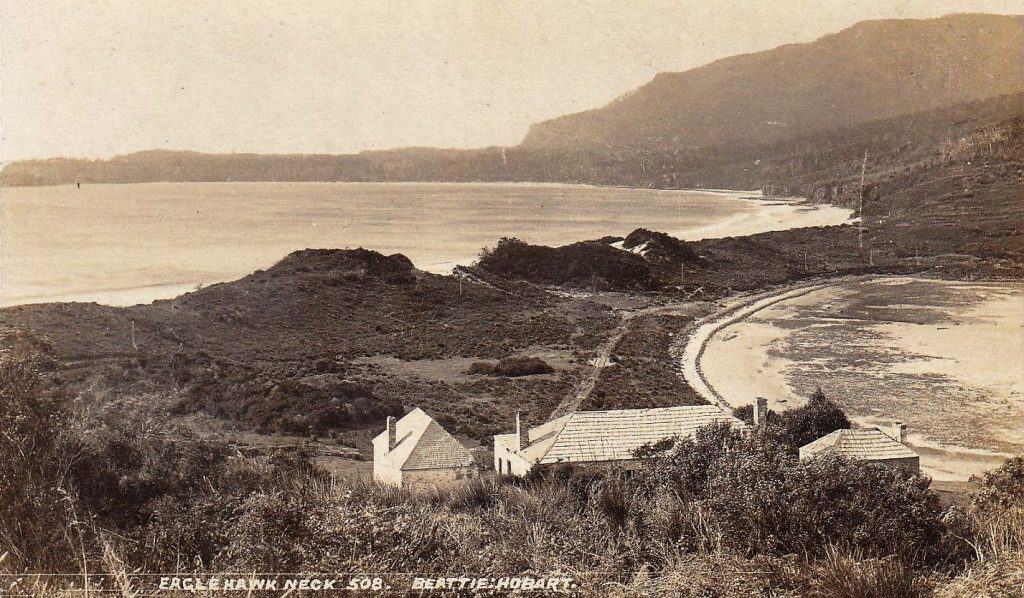

The narrow peninsula at Eaglehawk Neck stopped prisoners escaping. Picture: Aussie Mobs

The site was deemed naturally secure as it was surrounded by water, with the 30m wide isthmus of Eaglehawk Neck the only connection to the main body of the island. This area

was fenced and guarded by soldiers, man traps and starving dogs.

Nonetheless, some prisoners tried to escape.

One of the infamous incidents was by George “Billy” Hunt, who disguised himself in a kangaroo hide. When hungry guards tried to shoot him for dinner Hunt surrendered, and received 150 lashes.

Port Arthur was also a destination for juvenile convicts, receiving boys as young as nine. They were separated from the main convict population and kept on Point Puer.

Despite the new view of correctional imprisonment, Port Arthur was harsh.

Prisoners were believed to have murdered inmates to win their own execution, to escape the prison.

The Island of the Dead was the destination for those who died. There are 1646 graves recorded, but only 180 are marked.

The prison closed in 1877.

As early as 1842 the area was recognised as a potential tourist attraction.

Port Arthur today. Picture: Andrew Braithwaite

Ghost stories gave added popularity to the ruins, as did novels For the Term of His Natural Life (1874) by Marcus Clarke and The Broad Arrow (1859) by Caroline Leakey.

In 1979 funding was provided to preserve the site as a tourist destination, because of its historical significance.

On April 28, 1996, the Port Arthur site was the location of a killing spree. Deeply disturbed Tasmanian man Martin Bryant killed 35 people and wounded 25 more before being captured by police. Bryant is serving life in the psychiatric wing of Risdon Prison in Hobart.

Visitors can survey the Port Arthur site themselves, or join guided tours, including a harbour cruise, tours to the Isle of the Dead and Point Puer, and evening Historic Ghost Tours.

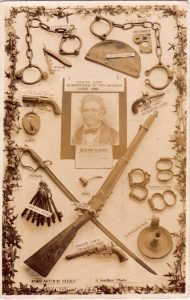

There is a museum with written records, tools, clothing and other convict items, a Convict Gallery, and a research room where visitors can check for convict ancestors.

Visitor facilities include two cafes, a bistro that operates each evening, gift shop, and other facilities.

Port Arthur was not Tasmania’s only penal settlement.

The Macquarie Harbour Penal Station was established on Sarah Island in Macquarie Harbour between 1822 and 1833. It took on the worst convicts.

During its 11 years, it earned a reputation as one of the harshest penal settlements, second only to Norfolk Island.

The former penal station is on an 8ha historic site on Sarah Island. The station took the worst convicts because it was surrounded by a mountainous wilderness many miles from settled areas.

The remains of Port Arthur. Picture: Harshit Sekhon

The only seaward access was through the Hells Gates channel.

Neighbouring Grummet Island was used for solitary confinement.

Despite its isolated location, some convicts attempted to escape.

Bushranger Matthew Brady was among a party that escaped to Hobart in 1824, after tying up their overseer and seizing a boat.

James Goodwin was pardoned after his 1828 escape and was then employed to make official surveys of the wilderness he passed through.

Sarah Island’s most infamous escapee was Alexander Pearce who escaped twice. On both occasions he ate fellow escapees.

Punishment for prisoners included solitary confinement and regular floggings.

There were 9100 lashes given in 1823.

The site was closed in 1833. Most of the remaining convicts were relocated to Port Arthur.

About 75,000 convicts were sent to Van Diemen’s Land, as Tasmania was then known, before transportation ceased in 1853.

In 1854 the Constitution of Tasmania was passed and in 1855 the name Tasmania was officially recognised.

In 1901 Tasmania became a state through the Federation of Australia.

Tasmania is 240km to the south of the Australian mainland, separated by the Bass Strait.

Remains of the Sarah Island penal structure. Picture: Owen Allen

The state now encompasses the main island, the 26th-largest island in the world, and 334 surrounding islands.

In 2016 the state had a population of about 519,100, about 40 per cent of whom live in the Hobart precinct, the area around the state’s capital city.

Despite years of forestry Tasmania and agriculture, including a once thriving fruit-growing industry, much of Tasmania remains in a natural state.

The island’s protected areas cover about 42 per cent of the land area, which includes national parks and World Heritage Sites.

Tasmania was the founding place of the world’s first environmental party, a result of the controversial damming of Lake Pedder and a subsequent unsuccessful push to dam the Gordon River.

The Bishop and Clerk Islets, about 37km south of remote Macquarie Island, are the southernmost point of the state, and the southernmost internationally recognised land in Australia.

Famous Tasmanians include the princess Mary Donaldson, naturalist and miner Deny King, Hollywood actor Errol Flynn, bushranger Martin Cash, champion woodchopper David Foster, politician Josh Lyons, sporting personality Max Walker, composer Peter Sculthorpe and author Richard Flanagan.

Tasmania Today

Tasmania is now a thriving state with a mix of industries, including tourism, forestry, agriculture and aquaculture.

Many Tasmanians appreciate the island’s natural heritage, which has caused conflict with extractive industries, particularly forestry. Clearfell of old growth forest and the burning off of cleared areas are particularly controversial, as is intensive fish farming of Atlantic salmon.

What will the future bring?

It is likely Tasmania will grow strongly, as mainland retirees sell their high-value homes and move to Tasmania to purchase cheaper properties, providing an opportunity to put substantial cash into retirement accounts, and escape mainland heat.

Tasmania may become something of a climate refuge in future.

However, the island won’t escape the ravages of climate change, with predictions that it will become hotter, drier and windier.